Evangelism often centers around pragmatic approaches – what works and what does not work. Pragmatism bears programmed material, automatically-generated responses, and destroys the authentic, the divinely-inspired, and the truly miraculous.

I continue to return to Stark, for which I ask the reader’s forgiveness. But Stark, as a secular writer, encompasses the modern religious and categorical systems of Christianity in a way that sharpens the incongruence of the organic and unregimented growth of the early church and present day missionary programs and plans.

“Religious testimonials…can recount experiences of personal regeneration that followed conversion or renewal – victory over alcoholism, drug dependency, or marital infidelity. In more dramatic fashion some testifiers can claim to have benefited from miracles – supernatural interventions that averted catastrophe or provided inexplicable healing. In this way people offer evidence that a religion “works” and that it’s promises must therefore be true.” (Stark, 173)

Testimonies encourage, build up, and, in some cases, transform the hearer. But, as Stark explains, testimony merely alludes to the pragmatic, fix-your-problem-now culture that plagues the modern church’s understanding of holiness and discipleship. We desire immediate conversion. Immediate character transformation. Immediate breakthrough and desires fulfilled.

Albert Camus, the 20th century French novelist who centers his writing on “the absurd,” creates an encounter between a convicted murderer and an interrogator in his work “The Stranger.”

“From across the table he had already thrust the crucifix in my face and was screaming irrationally, ‘I am a Christian. I ask him to forgive you your sins. How can you not believe that he suffered for you?’ I was struck by how sincere he seemed, but I had had enough…In a low voice he said, ‘I have never seen a soul as hardened as yours. The criminals who have come before me have always wept at the sight of this image of suffering.’ I was about to say that that was precisely because they were criminals. But then I realized that I was one too” (Camus, 69-70).

In typical Camus fashion, his character lives a strictly observational, non-judgmental existence that wards him away from meaning. Yet, this man enters into a principal Christian understanding – a profound realization of his own depravity. Tragically, the interrogator’s burning for the murderer’s immediate conversion comes from his longing for personal glory, a desire for commendation and acclaim that credits his ability to evangelize. He even cites the other criminals’ supposed repentance in order to esteem himself. Like many of us in the West, his own thirst for control, power, and approval prevents him from effectively sharing the Gospel.

Our understanding of evangelism rests on the efficacy of our own presentation and methodology. If it “works” in a given context, many immediately replicate it. This explains the phenomenon of the ultra-modern, chic, and relevant churches that the West continuously churns out. It additionally underscores our inability to present the Gospel correctly ourselves, rather than depend on a “cool” church and a “charismatic” pastor to do the work that God asked us to do ourselves in the power of the Holy Spirit.

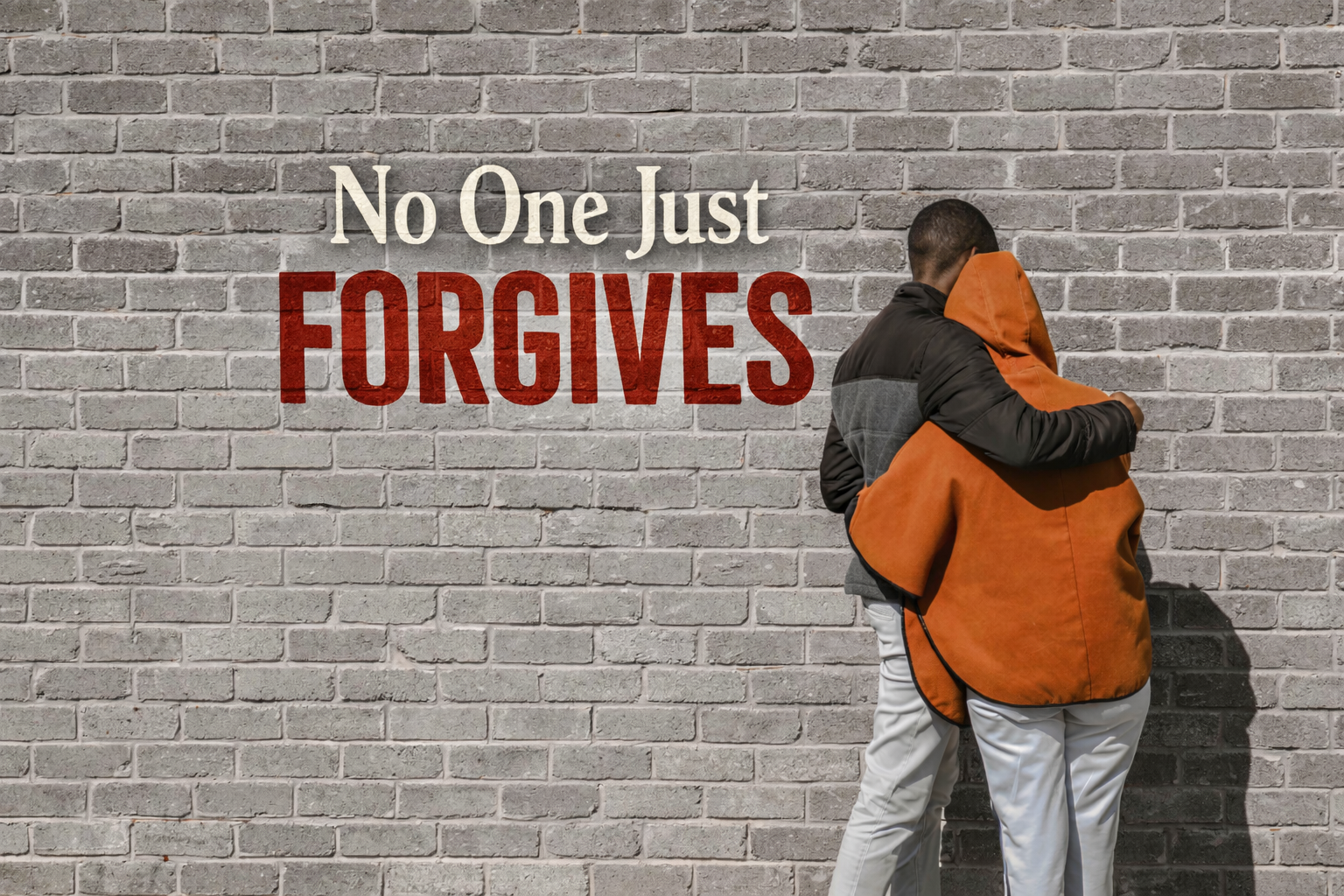

Biblical evangelism centers on God. It demands an understanding and submission to the mystery of salvation demonstrated in Scripture, “So then he has mercy on whomever he wills, and he hardens whomever he wills” (Romans 9:18). We follow the way of the Master. Love is longsuffering (Galatians 5:22, Ephesians 4:2). Discipleship goes to any means necessary. We take up relationship, patience, grace, mercy, power, and persistence in the same way in which they marked those in the early church. If the LORD leads us through the narrow gate, then we must walk the hard road that follows. He designed it that way.